the Mangrove Nine

From bringing the historical event to

the screen to costume designing with authenticity

Words Sean Stillmaker

People of colour being discriminated, protesting police brutality and battling racial injustice in the courts — all of this sounds as commonly heard headlines today, and is as unfortunate since it was the same 50 years ago.

A beacon of triumph for the struggle in Britain came in 1971 with the trial of the Mangrove Nine, and just as poignant as the above reality, it’s a story that’s been marginalised to footnotes in British history.

Frank Crichlow immigrated from Trinidad in 1953. Settling in west London, he began working for British Rail and then transitioned to an entrepreneur starting with a café in Notting Hill and then opening the Mangrove restaurant at 8 All Saints Road in March 1968.

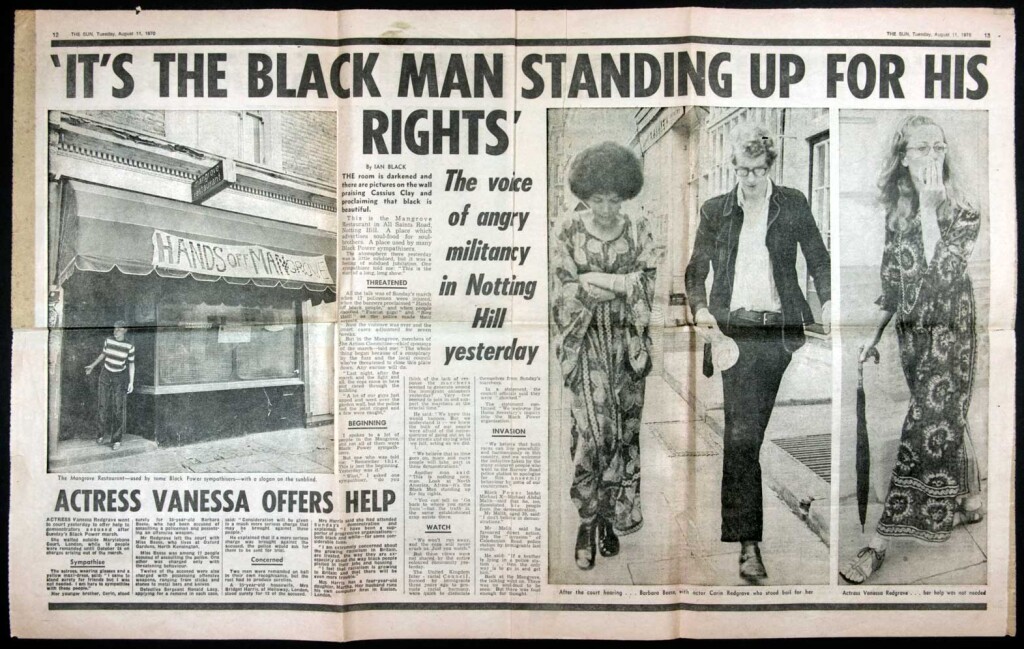

The Mangrove was a lively late-night haunt serving locals, activists, intellectuals and artists, such renowned visitors ranged from Diana Ross and Jimi Hendrix to Vanessa Redgrave and Sammy Davis Jr. As Notting Hill had become London’s Black-culture capital, the Mangrove served as a de facto community hub where people came for advice on things like housing or job applications.

Discriminatory and heavy-handed policing, however, ravaged Frank and the community. Police led consistent raids of the Mangrove, looking for drugs, which they never found. The local council then restricted Frank’s operating license, which devastated his earnings.

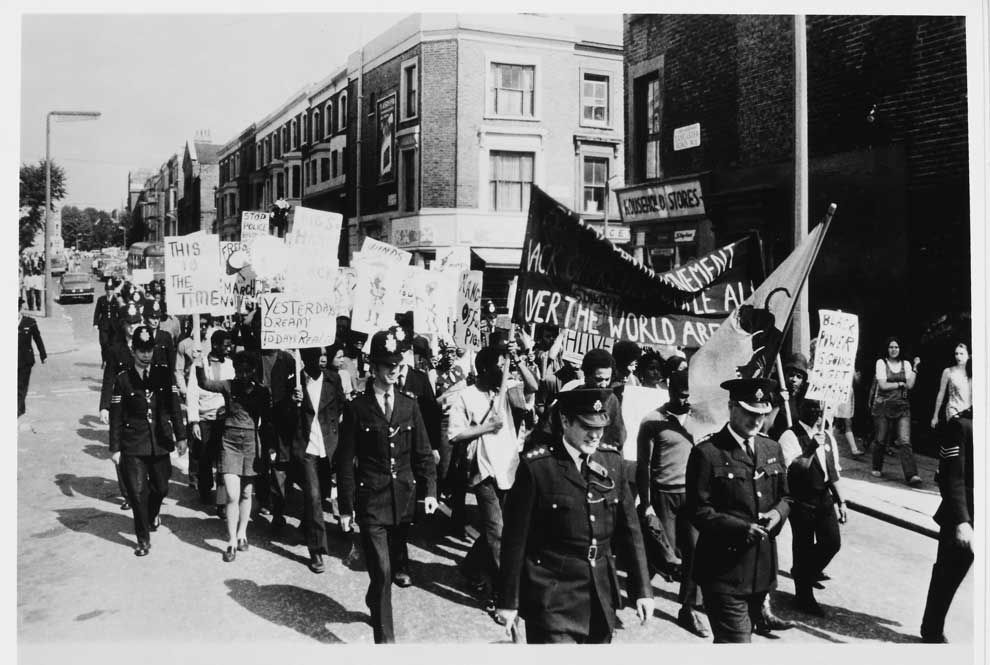

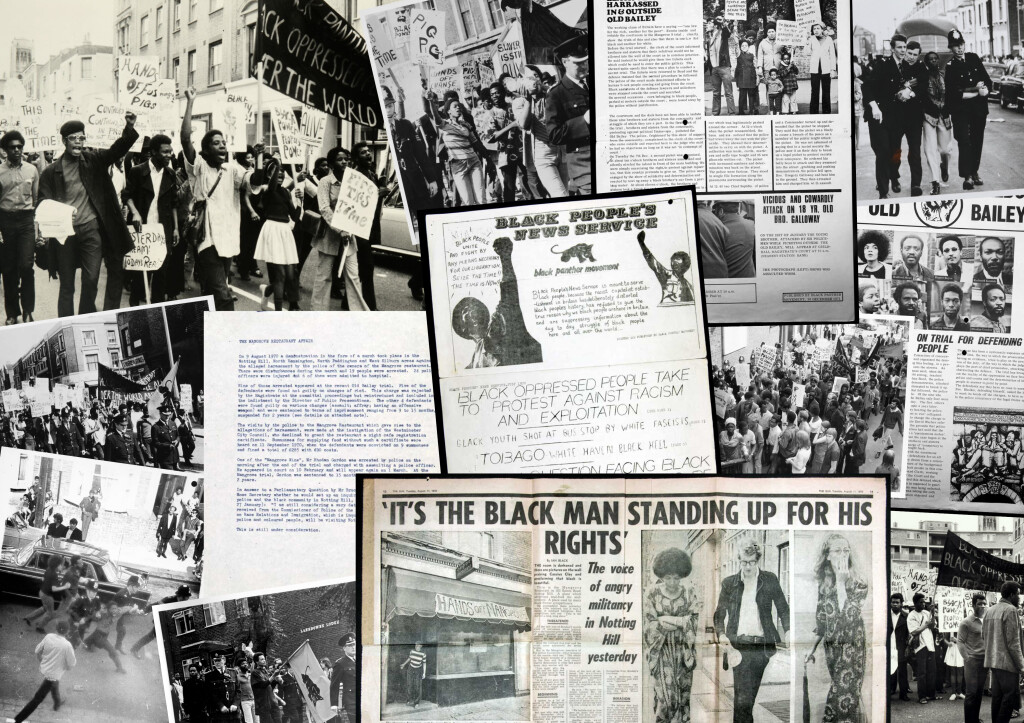

With no other options, Frank and the British Black Panthers led a protest march on 9 August 1970. Intended to be peaceful, it soon escalated into a violent encounter where numerous protestors and police were injured. Frank, alongside eight others, including British Black Panther leader Altheia Jones-LeCointe, were arrested and charged for incitement to riot in addition to other lesser offenses.

After a 55-day trial at the Old Bailey, a historic ruling was given where the Mangrove Nine were all acquitted of the principal riot charge; five of the nine were acquitted of all charges with the remaining given suspended sentences for lesser offences.

It was Judge Edward Clarke’s closing remarks, however, that made it so historical where he said the trial had, “regrettably shown evidence of racial hatred on both sides.” A further impact of the trial’s favourable outcome led to the formation of the 1976 Race Relations Act, which was a step closer to racial equality.

But the successes won here in the 70s faded from memories and are overshadowed by the white narratives taught in education curriculums.

To be immortalized in film, ensuring we never forget again, director Steve McQueen has delivered justice dramatizing this story in the feature film Mangrove, which sits as the first chapter in his Small Axe anthology series where each of the five films focus on a West Indian experience in London between the late 60s and mid 80s.

“They are just as much a comment on the present moment as they were then,” writes McQueen in his director’s note of the films. “Although they are about the past, they are very much concerned with the present. A commentary on where we were, where we are and where we want to go.”

From the onset of production, McQueen mandated the diversity shown in front of the camera to be reflective behind the camera as well. For Mangrove Costume Designer Lisa Duncan the story deeply resonated with her, growing up as a child in the 70s with a mother from Portugal and father from the Caribbean, she would spend her time with her grandmother in a very similar Caribbean community in south London.

But very much like the many, the story of the Mangrove Nine was something unfamiliar to her. “These stories have just been swept underneath the carpet,” says Lisa. “It was not something that has been written about much at all, really, so I was just fascinated to hear about this court case.”

Although diversity on both sides of the camera was achieved, the struggle to get there is very much a commentary on our present. “We tried; every single department was told to try and get 50 per cent diversity, but truth is, there aren’t enough people working in the industry,” says Lisa.

When crewing up in the spring of 2019, Lisa extensively searched inclusivity with costumiers, but the problem was availability. “Everyone is trying to increase the diversity, which is great, but it means the few people that are in the industry are working nonstop,” says Lisa. “There is a lot more diversity in fashion and music, and I think it’s just one of those things, in this country, it’s not as well known — the journey and the path to get into the film industry as it is in America.”

After production wrapped, some of the girls that worked on Lisa’s team started the Black Costume Network. The group is a place for under represented voices focused on positivity and progression that not only is a professional networking platform, but a resource for education and training for the next generation of costumiers.

As Lisa stresses, “you need to train and learn,” because costume designing is very different from fashion. Lisa’s journey originally started with fashion and bridged into commercials. She then went back to university, receiving an MA in costume design. “People don’t realize how different it is. When you’re faced with designing something like this, the budgets are huge, that’s my responsibility to, to work out how many crew we need.”

The tipping point in terms of both the real timeline of events and the film’s most complicated shooting day culminated in the protest march. Working fulltime on Lisa’s team were eight people, but on the protest shooting day, there were 20 on her team alone. Then of course there were the months of all the work that led up to make that day as authentic and seamless to capture. Between the principal cast and background artists, there were approximately 250 – 300 people to wardrobe on the protest march alone.

As authenticity was paramount to achieve, 75 per cent of the costumes seen in the film are original pieces from the period, Lisa says. The remainder are period replicas or copies from original garments that were found, but were either not the right colour or wrong measurement for the actor, so the team had the piece made.

Some of the costumes were rented from costume houses like Angels and Bristol, but for what couldn’t be rented was supplemented with vintage shopping. Although the Mangrove on All Saints Road in Notting Hill closed in 1992, the adjacent Portobello Market a couple blocks away still thrives today. As an anchor for the neighbourhood, the market continues trading with its array of antiques and vintage fashion.

The vintage traders were instrumental in sourcing, but as Lisa recalls from the beginning telling them about the production, they really did not know the local story of the Mangrove Nine either.

With character mood boards and historical research photographs, Lisa sought an authentic and distinct look for the period. “They could quickly see it wasn’t stuff for parties, it wasn’t usual 70s disco, nothing like that, it was very much everyday clothing,” she says.

As clothing of the period has been in and out of fashion for years, actual garments from the 70s are very different from today especially in terms of cut. “People were smaller then, generally, because they ate less. So the trousers were high-waisted and quite fitted, that’s not a style that’s not worn as much now,” she says.

There were men’s clothing Lisa found, but the waist started at 26, which is more of a woman’s size. She’s then trying to wardrobe a 21st century male, which can have more muscle mass, so finding bigger sizes that could disguise the shape is useful.

For Letitia Wright, who plays British Black Panther leader Altheia Jones-LeCointe, to get into character, it was the combination of costume, hair and speaking the accent that was instrumental. “Definitely the clothes did something, even the undergarments they wore back then,” said Letitia during a screentalk.

The undergarments are a detail that did not even show up on screen, but that was the extent Lisa and her team went into considering complete authenticity. The undergarments used were vintage styles bought from a company that was active making them then, says Lisa.

“There were some garments [Letitia] felt might be too old for her character for the courtroom scenes, one in particular, but then I showed her the references, and they weren’t. It’s just she wouldn’t know the costumes that well, like the older actors completely got it,” says Lisa. “They would say, ‘oh my god my dad used to dress like this’ or ‘my aunties dressed like this.’ Llewella [Gideon] who played Aunt Betty said, ‘I can’t wait for my aunt to see this because this is them, this is how they dressed.’ Shaun Parkes said, ‘I remember my father and his friends and they were always well turned out; they never wore anything that was worn or had holes; they always dressed to present themselves.’”

One of the most complicated costumes to design though were the police uniforms. Not every production receives London’s Metropolitan Police authorisation to display their branding, which was the case here. So the badges worn by the officers had to be specifically designed and created for Mangrove, which is a rigorous and bureaucratic review process.

Although historical documents indicate that on the protest day there were approximately 700 police made available to cover the event, the production only had 120 uniforms because, “that’s the most we could get,” says Lisa. “It would have been virtually impossible to get [that many] uniforms. We would have to get those made and that process would have taken six months.”

The idea to bring Mangrove and the Small Axe series to life was originally planted 11 years ago, but as McQueen progressed its development he soon found the distinct narratives to turn into five individual films.

The series name of Small Axe refers to the West Indian proverb that means together we are strong — if you are the big tree, than we are the small axe. With Mangrove and the second film in the series, Lovers Rock, selected into the Festival de Cannes, McQueen has dedicated both to George Floyd and “all the other Black people that have been murdered, seen or unseen.”

Related Reading

@majesticdisorder

@majesticdisorder