FILMING FOR PEACE

Kate White in conversation with filmmaker Benjamin Gilmour

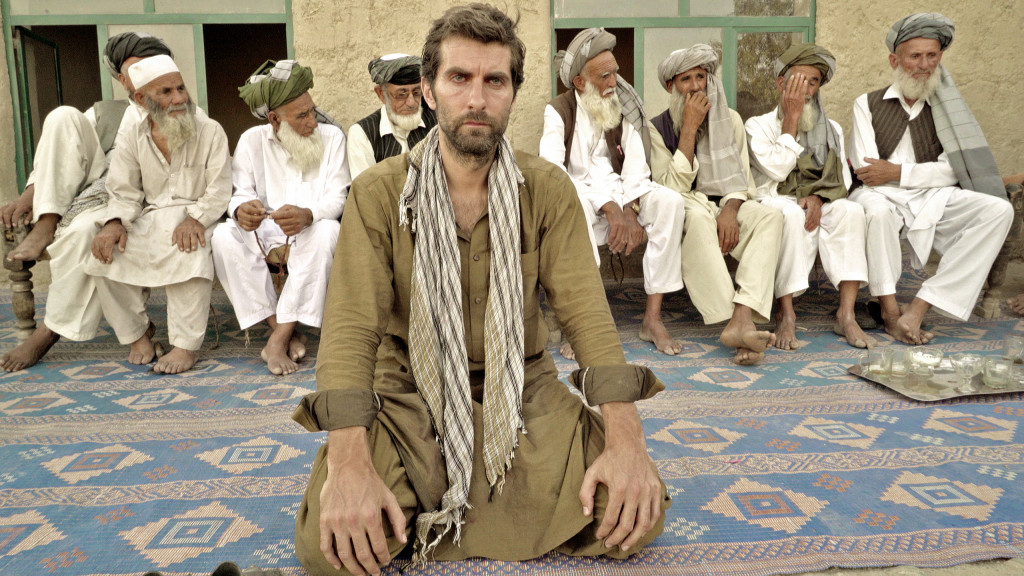

Benjamin Gilmour is an Australian filmmaker and writer. His film Jirga follows the perilous journey of an ex-soldier as he travels across Afghanistan, seeking forgiveness from the family of a man he shot and killed during a raid three years earlier.

In a story that echoes the filmmaking process, Benjamin talks to us about their journey across the dangerous landscape of Afghanistan, negotiating countless obstacles and risks in order to make a film that reveals the devastating impact of war and its emotional consequences. Exploring themes such as forgiveness, justice and compassion, Jirga shines a healing light on fractured lives and demonstrates the power of storytelling to inspire peace in war-torn places.

What was the spark of inspiration that led to making Jirga?

There were so many factors involved. My journey as a writer and filmmaker have taken me to Pakistan, Afghanistan previously, for the beauty of the nature and the people. Also, it weighed on me for sometime being witness to the destruction and suffering of war on Afghanistan. Having made friends among Afghans on previous visits and then as a paramedic of 20 plus years, which is what I’m qualified as and still work as part time in Australia when I’m not making films and writing, coming into contact with veterans returning from that conflict. So many of them are traumatised, (and have) broken marriages, relationships, drug and alcohol issues, so all of that, it’s like the perfect storm really leading to Jirga’s coming about.

One night, when I was working as a paramedic in Sydney I came across a gentleman who was living rough on the streets of Kings Cross, which is our kind of red light district in Sydney. He was feeling psychotic and was in a really bad way and we had to take him to hospital for psychiatric care. He told me a story in the ambulance about having been in the army, and being part of a raid on a village where he was based, it was a joint operation, a night raid, and he said that he shot someone, and it had stayed with him and messed with his head, and yeah he’d lost everything after leaving the army.

I started to think about the impact of war on veterans as well as civilians and I knew from having spent many days, weeks, months in tribal areas of Pakistan, making Son of a Lion, my first film, and having spent time with a guy who had such great knowledge of Afghan history and tradition, he taught me all about the tribal code of conduct known as Pashtunwali. I remembered that if one of your enemies comes to your door to apologise for a crime against you, you are obliged within this tribal code, to forgive them and not only forgive them but to welcome them in and give them shelter.

I asked myself the question – what would happen if a soldier went back and apologised to a family of a civilian he had killed? It was pondering these things and getting back in touch with some of my Afghan friends to ask them about how they would see that kind of scenario play out as a soldier returning. They all agreed that if there was genuine remorse that forgiveness was possible.

What were the most challenging aspects of making this film?

There were plenty. Initially I think the challenge of dealing with the bureaucracy in countries like Pakistan. That is where we first tried making Jirga in Pakistan because I thought there is no way an Australian actor is going to shoot a whole feature film in Afghanistan, a country at war. Part of the contract I actually signed with Sam Smith’s agent was that there would be virtually no shooting in Afghanistan, apart from if the security conditions were improved there may be allowance for a few days shooting with high level security.

So just dealing with our initial hosts, our primary hosts in Pakistan. I suspected that they had a file on me from my previous visits to the country but I didn’t realise how thick that file was. We were not only not given permits but we were harassed and hounded by secret agents who tailed us James Bond style through the streets on motorbikes and hiding in bushes. It was very intimidating. So that was an element dealing with that bureaucracy. We went through to Afghanistan to see if we could make the whole thing there, which Sam did without telling his agent or his mother, which was probably a wise thing.

What was it like filming with so much risk to your personal safety?

When we were shooting in the caves and the mountains around Jalālābād, I’ve never sweated so much as when we were sandwiched between cops with an army escort through Jalālābād city under lights and sirens. So having travelled through that part of the world before I knew this was very unwise and yet we were kind of at the mercy of this security escort and I was worried about being ambushed, which was a real possibility. It didn’t help that one of the very few foreigners left in Jalālābād at that time was an Australian aid worker who was kidnapped the day before we arrived. I had the Australian ambassador, phoning me every day saying, “you’ve got to get out, we’ve got specific threats against you” and yet we had this film to shoot and we were half way through.

In drama you can’t walk away because you’re shooting a sequence and the whole story just won’t work. So I had the pressure of we’ve got to finish this film but there were these specific threats. I said if you want us to get out quicker you can do one thing for us, you can pass our shooting coordinates to the Americans and the Afghans so we don’t suffer friendly fire, because that was a real risk in the mountains around Jalālābād.

How did the challenges influence you and your creative process?

You know what these obstacles, they kept escalating as we got closer to our goal of achieving this film. All the while the time was ticking and the obstacles were just getting more intense and the danger was getting more intense and I was becoming very despondent, as the time was ticking that we wouldn’t get everything we needed to get before we needed to leave. But it occurred to me that these obstacles mirrored the hurdles that our protagonist was facing. That this soldier, ex-soldier, Mike Wheeler, returning to Afghanistan, as he was getting closer to the village where the raid had taken place, where he wanted to apologise to the family, we were getting closer to the end of the shoot.

At one point, I had this light bulb moment where my eyes were opened to this idea that we were in our own parallel film or universe, that these journey’s were connected. We needed as filmmakers, we needed to go through this with our protagonist and suffer with him on this journey and get through those obstacles and that those obstacles were part of it all. If we didn’t experience those, then his experience wouldn’t be as authentic.

I think looking back there was a truth in that because by the time Mike gets to the Jirga which is the circle of elders, which is the tribal court which he faces for his crime, Sam Smith, the Aussie actor I was with, he was in a real state and what you see on screen is what he was pretty much like. He was wrecked and that’s why people say his performance was so convincing in that moment because he wasn’t too far from the truth.

What helped you to get through the most difficult moments of filming?

I definitely felt like I was a vessel for something really important and much greater than all of us, and that we were all being used by this positive force for peace that was working through us to create this really important, to give birth to this really important film, to be in the world to inspire people and to help people think differently about conflict.

I wouldn’t call myself religious, but just from my life experiences to date I feel that my hands have been guided – there is something bigger at play. I can’t explain it, I can’t put a name to it, I’m just conscious of it and that’s the way I love to create. It’s kind of submission. It’s this kind of surrender.

What does the film represent to you?

For me Jirga is about how human beings reconcile their guilt or live with their guilt and what they do with it, because guilt is something that kills people. Guilt can kill, it can eat away at people’s lives, it can manifest in broken relationships and addictions and even more tragically suicide. Jirga asks the question what would you do if something that wounded someone so deeply either physically or emotionally resulted in a death?

Jirga is also about the idea of justice. I lost faith quite a long time ago in the notion of good people and bad people because I think we all have good and bad in us, and unfortunately films, in particularly Hollywood films, still very much lean on this black and white idea of goodies and baddies which I think doesn’t do us any favors as humans. So I’m a great advocate of restorative justice, which has existed in Afghan culture for more than 2,000 years. Through this film I want the viewer to deeply understand the importance of the possibility of forgiveness – how to forgive others and how to forgive ourselves.

Healing is possible. To release that weight is achievable and I feel such deep sadness for people who have taken their own lives, or who have slowly died because people die slow deaths through this kind of suffering of guilt. I feel such sadness because healing is possible, it’s achievable and here’s an example in this film of how its achievable. Yes, sometimes it must take a bold step, sometimes it requires a bold step to achieve but it is there. The film, at its heart, is about forgiveness.

Related Reading

@majesticdisorder

@majesticdisorder