Adapting ZOLA

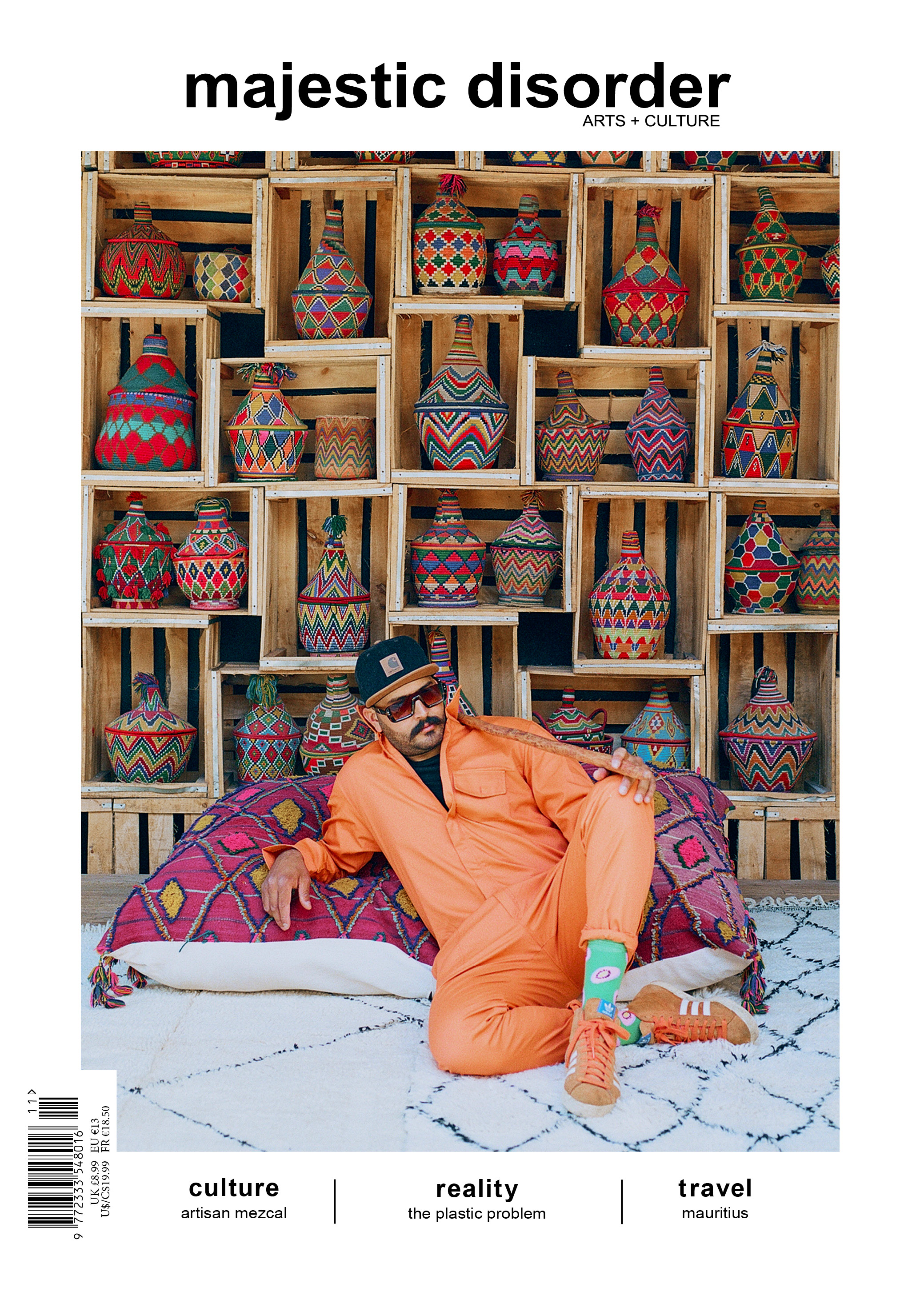

Sean Stillmaker in conversation with filmmaker Janicza Bravo

In October 2015, A’Ziah “Zola” King posted a story on her Twitter. Before there were threads, the then 19-year-old posted 148 tweets detailing, “why me & this bitch here fell out,” read Zola’s first tweet.

Zola was working as a waitress who also dabbled in stripping. Upon befriending a customer, “vibing over our hoeism,” Zola tweeted, she was convinced by ‘this bitch,’ under false pretenses, to take a trip to Florida to work dancing together.

Little did she know, the Twitter narrative detailing her tumultuous journey from Detroit to Tampa in 48 hours would go viral. Salacious and sensational, Zola’s story encompassed a raw and intimate look into the rarely seen laissez-faire of sex work that also involved a nameless pimp, an idiot boyfriend and some shady Floridians.

Rich with humor, Black Twitter specifically called Zola’s narrative, The Thotyssey, the first big poem of the digital era being compared to the epic Greek poems of Homer. You can read the original Twitter story here.

The Twitter story read like a cinematic roller coaster ride, so it was inevitable it would land on the screen. If handled by lesser hands, Zola’s epic poem may have been forgotten in the fringes of the internet, but director Janicza Bravo and her co-writer, esteemed playwright Jeremy O. Harris, have manifested a truly wondrous film that not only honors the original text but also delivers a thrilling experience reflecting on our contemporary culture, language and the nuances of sex work.

We sat down with Janicza to explore her journey in making this film that she says inhabits the genre of stressful comedy.

How did you first come across Zola’s Twitter story and was there any apprehension adapting tweets to a movie?

I read the story on Twitter the day it came out, not live because I’m not on Twitter. So I was not part of the live engagement, but I read it in the 24 hours that it came out. I’m a theatre kid through and through, so when I read the piece, my feeling was, if I’m going to adapt this, I want to treat it like I would any other piece of literature, which is to be as true to the text as possible — to uphold it in the way you would Chekhov, Ibsen or Shakespeare. So for me, just because it was on Twitter, I didn’t find that to be a less than medium.

What was your initial reaction to Zola’s narrative?

The original text was leaning more into the ride and the party and I wanted to engage with the trauma. When I read the text, I just felt there was a lot of trauma in it. There was a good deal of humor, which is why I felt I was right for it, but had there not been the humor, I don’t know if I would’ve been the right director to spearhead it. But behind the curtain of that text is traumatization; it’s a survivor processing this really horrific experience.

How did you want to embody Zola’s reality and what was challenging from adapting her as a protagonist?

Zola is 19 when she writes the story. Taylour (Taylour Paige playing the part of Zola) is not 19, you probably noticed, but I had a sense that some portion of the audience would arrive at the story struggling to get on board, struggling to believe her because we have a hard time believing women and we really have a hard time believing Black women.

My one assignment was to be true to [Zola’s] voice, and the women she introduced me to [and my collaborators to]. This is the world as she presented it. The film is not journalism and it’s not documentary. She never looked at them with judgment. What she judged was the situation she was pulled into, not the work.

[Zola] made it very clear to me early on, because she as a 19-year-old who was working in sex work, she made it clear, ‘I don’t come from a fucked up background. I have not found myself in this because my life was so hard, or because I didn’t have opportunity. I wanted to be in this. I was turned on by this world and I had a certain relationship to my body and to sex and I wanted to play in this space.’

I had not met anyone like this, definitely not on screen who had been inside sex work and who had that amount of agency and comfort. And that’s going back to the Pam Grier of it all (Grier’s ’73 film Coffy was an inspirational reference point) — how can a woman stand so much in her voice but also still have a great rack.

Before you came on board, James Franco was developing the movie. How different was that script to what you wanted to achieve?

The original script was ‘leading with its dick,’ I’m glad you reminded me of that (referencing a quote Janicza gave to Rolling Stone). It was just much more naughty than what I was looking to make. In the first 20 pages, if I recall, I think there were four scenes of nudity. I don’t know if the audience is ready to talk about sex work and sex trafficking when we’re meeting women in the buff. I don’t know if our brains can all the way handle that.

I feel the film is also saying that trafficking is something that is happening in the United States; it’s happening right next to us; it’s at the house next door; it’s in the car next to you on the road. It does not look like this one specific thing we decided — there’s more nuance to what that world could look like and who it happens to.

Riley Keough plays the character of Stefani with a blaccent. Can you elaborate on the complexities and consideration that was given to this controversial choice.

Riley is a minstrel; she is wearing a blaccent. She is putting on manner and mannerisms that we have associated with Black people, Black women, that have not been appreciated when in those bodies. But when they are taken on by white people and white women, there’s been a good deal of pleasure. In fact there are women who’ve made money off minstrel things that Black artists have not been able to benefit off of.

I don’t know who the real woman is that Riley plays. So in building all four of those characters, particularly the three that I didn’t have the life rights of, my co-writer Jeremy O. Harris and myself, used little bits of things that we could find in the Twitter thread because the Twitter thread doesn’t introduce you to those characters before, it tells you who they are that weekend. It tells you who they are for 72 hours. So we used colors from that to sort of define them.

This idea that I had with Riley’s character, to use sports terms, needed a handicap. So that’s how we arrived at her taking on this accent — there’s something violent about her embodiment of it, but it is also kind of fun and dangerous.

When we met, she had a sense that’s what I wanted because that writing was on the page. She said that she was worried she would be cancelled. I was like, and I am too. My feeling was we couldn’t apologize for it; we had to be on the precipice without the net.

We got a coach to help her with that accent and shaping that voice. I think she did this really beautiful job. I do feel she’s embodying something that is a bit hard to pin because if you’re taking too much pleasure in her performance, you’re asking yourself, ‘is there something wrong with me?’ I think both of those things can happen: I think she can do a great job and we can ask ourselves, ‘am I ok?’

You use an innovative device acknowledging the Twitter thread throughout the film. How did you come to that choice?

I knew that because the story was born out of the internet, it was also woven into it, and that the internet needed to be paid homage — there had to be these digital gestures. The Twitter whistle was something that was written into the script, and the idea behind that was when we use a piece of dialogue that was pulled exactly from the Twitter thread, the whistle is an homage to its original source.

As the phone is both the source material and crucial in facilitating action, you applied many innovative storytelling techniques where the phone hardly seems invasive, thoughts?

To me the film feels Brechtian [referencing German playwright Bertolt Brecht] in its expression. I was also looking at it as a physical piece of art — if I was making a physical piece of art hanging in a gallery it would need to be in conversation with the phone.

The characters are so tethered to their phones and their phones were also extensions of their personalities, like they each had a phone ring that was supposed to be a window into their character.

I also knew that I didn’t want to see a person texting on their phone; I knew I didn’t want to do inserts of phones because things like that make me want to jump out of the window. So I had to figure out what were the things that most titillated me.

As I said before, I’m a theatre kid through and through, so as we arrived to, ‘how do the women text each other,’ or ‘how do we text in our world,’ I was thinking about a theatre aside [a device when something is happening internally and the character invites us in]. So I took that and put it inside Zola.

This interview has been edited and condensed from a roundtable interview during Sundance London.

All photos by Anna Kooris, courtesy of A24.

Related Reading

@majesticdisorder

@majesticdisorder