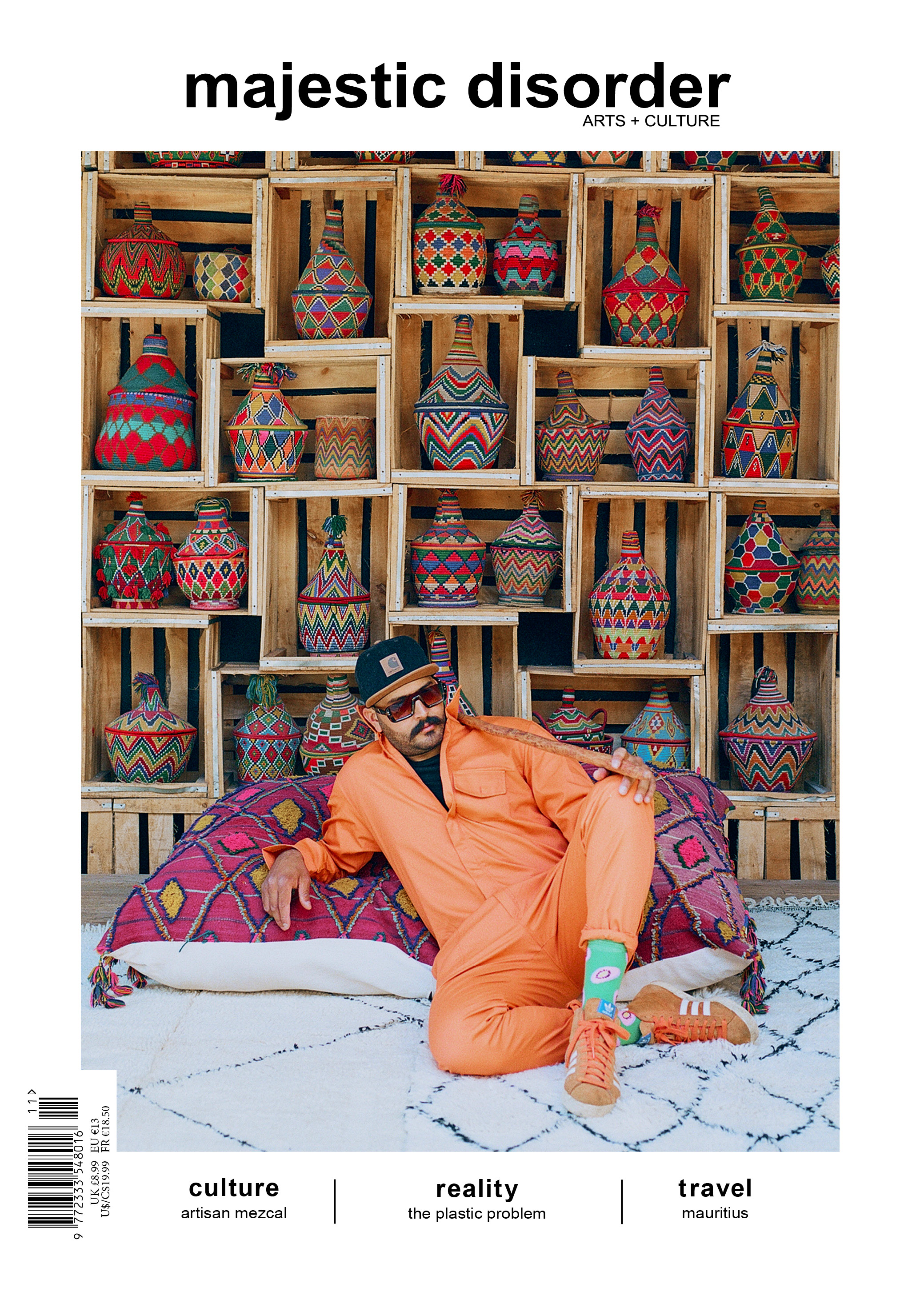

BEHIND THE SEAMS

Interview Sarah Garcia

Sarep + Rose founder, Robin, believes leather goods are more than just an accessory, they are the hidden gems of Africa’s artisanal craftsmanship.

Celebrating the raw talent of African tribes and makers, Sarep + Rose weaves together time-honored traditions with western styles, to create a collection of handcrafted leather accessories and textiles. After the loss of her own favorite bag in 2010, Robin was intent on recreating the design and in doing so she created a platform to share the undiscovered beauty of indigenous African cultures.

Drawing on the wisdom of her ancestral roots alongside her rich traveling experience, the founder spun the idea of Sarep + Rose. Through the use of raw textiles and entrepreneurial will, Robin and various artisan communities have brought together the latest contemporary styles with traditional artistry. Sarep + Rose promotes the preservation of authentic leatherwork and natural skill by producing handwoven, original and functional pieces, that showcase the creative spirit at the heart of African culture.

We sat down with the founder to discuss how she has intertwined organic ingenuity with the conformity of westernized style, and how she overcomes the challenges that come with operating such a unique brand.

You worked in the legal field, how did the idea for Sarep + Rose come about? What inspired you to connect westernized societies to indigenous artisan communities throughout Africa?

I hated being in the legal world, but after so many years and money spent focusing on that field, I felt trapped because I felt I had no other skills.

While brainstorming other more interesting things I could do, I remembered that people had always asked me to bring back bags for them. I felt like the beautiful crafts in Africa belonged to a ‘secret’ community of people like myself lucky enough to travel there and it shouldn’t be that way.

I founded Sarep + Rose after feeling frustrated with years of seeing so many quality artisanal African goods lay dormant for long periods of time. I decided that in whatever little way that I could, I would help to change that.

I also wanted to become part of showcasing the diversity of Africa, in the way a burgeoning group of African artists and designers already does incredibly.

Empowering entrepreneurs through craft in war torn areas is ambitious. Can you walk us through how this model works?

Almost every production cycle are a new set of lessons. I go to work with my artisans in person 1-3 times a year, to produce new designs or find practical ways to solve past problems in the manufacturing process.

The process is very different between my partners. The group I began this journey with is very traditional, from a West African tribe – the Fulani – known for their leatherwork for thousands of years. They’re working with the least resources and without electricity in their workshop, so everything is very hands-on. It’s challenging, but you can’t beat the feeling of when they produce something so beautiful out of what little they have.

Almost all of this BTS (behind the scenes) process is done via WhatsApp. I wouldn’t have a business without it! I send designs, get my fabrics sent over by a local employee and use photo messages to confirm colour combos with existing designs and prototypes for new designs. When I get to spend time with them, I spend time in the workshop to iron out product issues and finalize new items.

On the other end of the spectrum, my Kenyan partners are accustomed to trading more formally, and have many more resources to run a small factory. Working with them is mostly back and forth emailing and a lot of WhatsApp!

How do you maintain sustainability while also dealing with the constant risk of exploitation that comes with introducing artisan crafts into the global marketplace?

I work with my artisans in-person and buy each piece from them outright, which means they earn a premium but also places all the risks of selling on me. It’s definitely a hard way to do business, but they’re unable to take the same financial strains as an established factory could.

Recently, I started working with small factories. It’s something I’m always conscious about and find out as much as I can by getting to know the owners throughout the relationship. I have plans to go and meet the factory workers themselves in cases where I haven’t. If you announce your plans at short notice and they’re willing to receive you at any time – that is usually a good sign. When I move on to working with larger ones, which would carry a bigger risk of exploitation, I’ll have to personally meet the workers before I commence sourcing.

Sustainability means a sustainable business for my artisan partners. We are continuously learning from each other to work towards this. Through these exchanges I hope that I am on the path towards building a sustainable source of income for these entrepreneurs so that they and their families can enjoy some of the freedoms we often take for granted.

Sarep + Rose x majestic disorder

Related Reading

@majesticdisorder

@majesticdisorder