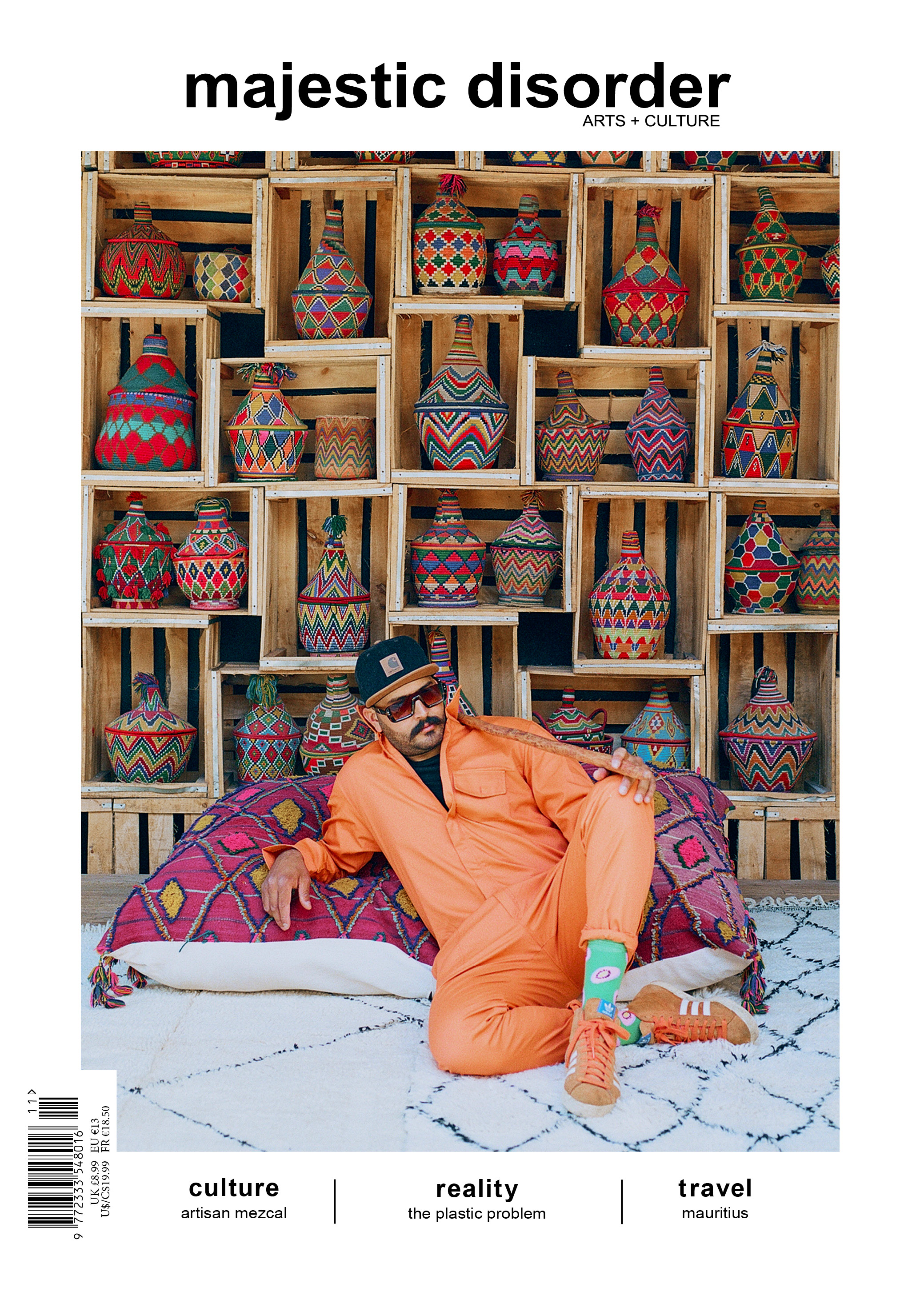

documenting culture

Words Sean Stillmaker

The Ghost Dance was a spiritual movement that swept across the Native American peoples in the late 1800s. Founded in peace, it was believed its ritual practice would awaken the spirits that would help bring peace and restoration of their native land and culture.

The US government saw the Ghost Dance as a threat used to incite uprisings, so they outlawed its practice in 1890. This led to the killing of Lakota Chief Sitting Bull at Standing Rock and then the massacre of hundreds of Lakota men, women and children at Wounded Knee.

It wasn’t until 1978 with the Indian Religious Freedom Act passed by Congress that Native Americans were legally allowed to practice the Ghost Dance and other rituals previously suppressed by the US.

Today, the Ghost Dance remains an empowering ritual connecting ancestral spirits with guiding wisdom to preserve our natural world.

Working towards communicating and preserving native cultures is Sinchi, an independent, self-funded nonprofit that works with indigenous communities around the world.

“Indigenous peoples have sought recognition of their identities, way of life and their right to traditional lands, territories and natural resources for years, yet throughout history their rights have been repeatedly violated,” says Sinchi Founder Tom Wheeler.

“The inheritors and practitioners of these unique cultures represent a continuum of intellect and creativity, which is often manifested through ceremony and storytelling with an emphasis on community, cooperation and a responsibility to protect the environment.

At Sinchi, we focus on providing indigenous peoples the tools to document their culture, preserve their knowledge and share their own stories with the outside world.”

With the Ghost Dance, for example, Sinchi has facilitated an upcoming project taking place at Rosebud Indian Reservation with the Lakota and Sioux people that explores the ritual’s history and impact.

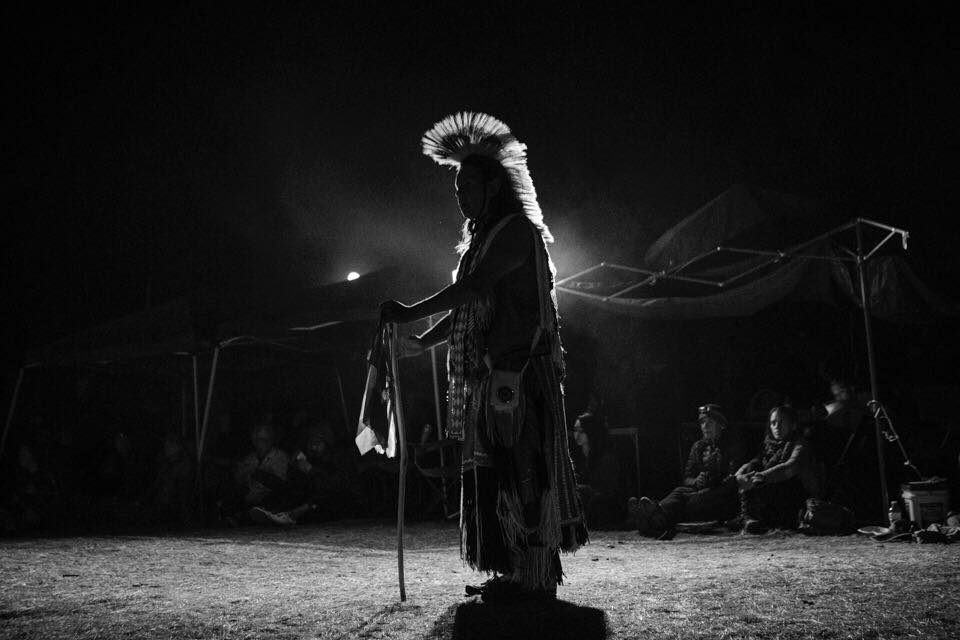

Leading the project is Michael Stuart Ani (shown right) who has extensively explored the roots of the Ghost Dance. Its introduction to Native Americans was pioneered by Wovoka, a shaman of the Northern Paiute tribe, but the Ghost Dance goes even farther back.

The Mazatecan Indians of Oaxaca, Mexico began the Ghost Dance thousands of years before. The ritual was born with the sacred mushroom sacrament, desheto, for the ancient god Quetzalcoatl.

The ritual then spread evolving with the various indigenous communities who incorporated their own intrinsic beliefs but the basic imprint preserving the connection between humans, their ancestors and the spirit of nature remained the same.

We sat down with Tom to elaborate more on some of the projects Sinchi is working with indigenous communities:

Can you tell us about the Sinchi Fund and two of the recent projects awarded funding?

The Sinchi Fund was created and is exclusively available to indigenous peoples who wish to document their own culture whether that be via photography, film, animation, audio or written form; funding ranges from €250 – 2000.

This year we have already awarded two grants, the first, “Documenting the Fa” in Benin.

To many of the indigenous peoples of West Africa, the Fa represents the soul of their culture. Fa is the means of communication with the gods and ancestors, speaking to them through a unique and complex system of 256 symbols, each symbolizing 16 parables and 16 local expressions.

However, local belief dictates that only the Bokonon can interpret the Fa Oracle and its meaning due to his knowledge of these 256 symbols — he is the one who talks to the realm of gods and ancestors and is thus presented with the answers given by the oracle.

Leon Gbaguidi of Savalou, Benin, is such a Bokonon (shown left). He is 85 years of age and drawing close to the end of his life on earth. His son Christian has been entrusted by the family to stand by Leon in his final years. It’s Christian’s wish to prevent his father’s ancestral knowledge of the Fa language to pass away with him.

To ensure the survival of local knowledge of the Fa Oracle, Sinchi has donated the required equipment to record Leon’s testimony and document this important part of their culture.

The second grant is working with the river people of Botswana (shown above).

The //Anikhwe are the only San Khoi group in southern Africa living closely connected to a riverine environment, just as the words: ‘//Ani’ (meaning ‘river’) and ‘khwe’ (meaning ‘people’) suggest.

This is why their traditional territories and cultural landscapes fall within the core zone of the Okavango Delta World Heritage site. Most of the islands found around the panhandle area of the delta are the ancient burial grounds for their rainmakers, and are thus regarded as highly sacred.

Menemene /A’niku and Tobo Zingoro are the descendants of the //Anikhwe leader and rainmaker N’ukhwa Kgebe, who lived with his people in the Okavango Delta and died around 1890.

With the advent of the Bantu-speaking tribes in the region, and the ensuing intermarriages and assimilation, the //Anikhwe tradition of rainmaking ended with the passing on of the last rainmaker, Kachire (the brother of Menemene and Tobo) in the mid 90s. The powers of rainmaking were passed on from uncle to nephew only, hence only the men could receive them. The same goes for the passing on of the //Anikhwe language, which is also in rapid decline along with cultural expressions such as dance.

It is therefore the wish of the //Anikhwe youth in Ngarange, Botswana, to document their peoples’ history in the form of documentary videography and on paper, including local knowledge related to fishing, medicinal plants and the preparation of food — all this to ensure the survival of the rich and ancient //Anikhwe culture for future generations.

Competition + Cash Prize

Sinchi will be hosting its second annual photography competition that explores the theme of cultural practice.

The entry categories are Documentary Series (up to 6 images), Portrait (single image) and Artistic Merit (single image).

Until August 15, entrants can submit their photos with accompanying captions that explores or is inspired by indigenous customs, events, spirituality and artistic expression.

The cost to enter is €5 for a single image or €10 for multiple images per submission, which all fees are donated to the Sinchi Fund. For those who do not have financial means to enter, complimentary entrance will be considered.

The panel of judges are looking for clarity of expression, overall artistic impression and potential for social impact. This year’s panel includes indigenous photographer Wayne Quilliam, international photographer Jimmy Nelson and last year’s winning recipient, photographer Josue Rivas; his selected photograph is shown below.

Up to 3 photographers will be selected for first prize that will receive €500. Up to 3 photographers will be selected for runner up, receiving €250. All will have their work shown in an exhibition taking place in Amsterdam.

Last year’s inaugural photography competition was extremely successful and left so many people feeling inspired by the work Sinchi is doing. What happened to the chosen winners and the impact Sinchi has had on their careers?

Yes we were overwhelmed by the quality of submissions and we received entries from all corners of the globe, which was really fascinating. This gained fantastic international press coverage and we subsequently hosted a gallery at leading Amsterdam cultural venue Pakhuis de Zwijger.

Much of the winners artwork has been sold — 50 percent going to the artist and the remaining 50 percent donated into the Sinchi Fund. On the opening night, we were delighted to have our 2nd place Delphine Blast attend, talk about her work with the Cholitas in Bolivia and her book which was commissioned on the artwork.

Our winner, Josue Rivas, went on to even bigger things and won the World Press Photo FotoEvidence Award which toured the world and was also published. Furthermore, Josue has become a good friend to Sinchi and amongst others things he is a judge for this years award and we are in talks about working on a project together.

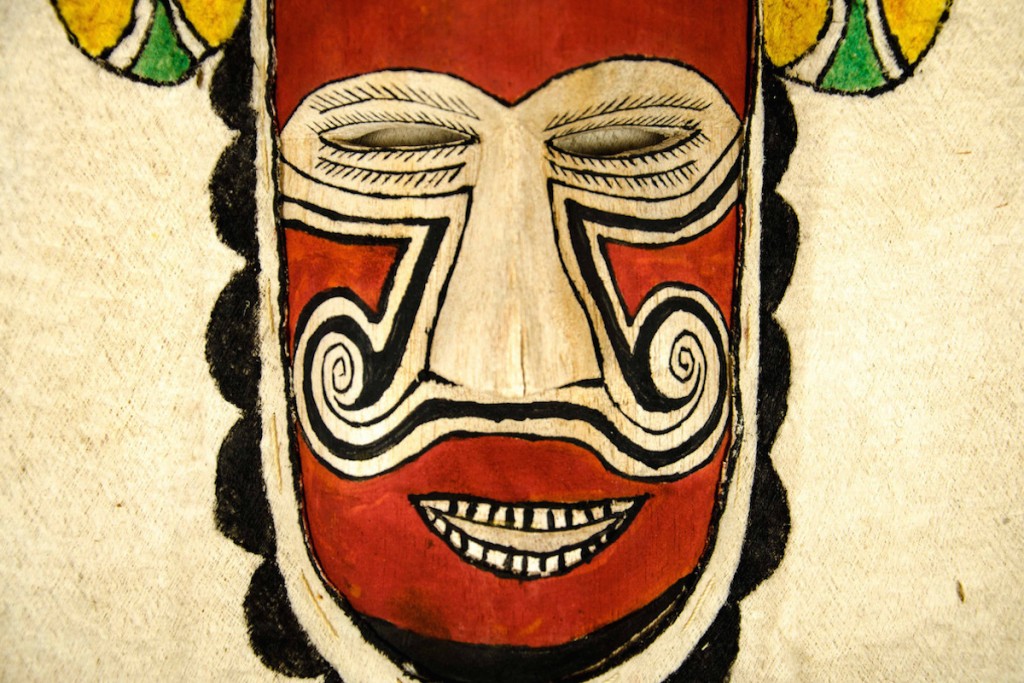

Finally and perhaps most exciting, came through our 3rd place recipient Chris Hopkins. Through his work documenting the Mentawai we were introduced to the Indigenous Education Foundation and have agreed to run a project, which will be widely held by both local schools and authorities to make sure Mentawai culture is preserved for future generation through reconnecting the communities on the island with their ancestral knowledge about medicinal plants, basket weaving, traditional Mentawai dance, storytelling and local mythology, language and hunting techniques.

Sinchi x majestic disorder

All black & white photography courtesy of Josue Rivas

Photo of Leon Gbaguidi courtesy of Herma Darmstadt

All other photography courtesy of Sinchi

Related Reading

@majesticdisorder

@majesticdisorder