remember chol soo lee

Words Sean Stillmaker

A wrongfully convicted Korean immigrant who was put on death row and a crusading investigative journalist who writes a series of stories that launches an entire movement of resistance by Asian Americans is the nut graf, as we like to say in journalism-speak, of the documentary Free Chol Soo Lee.

Although this story poignantly sounds contemporary, the events unfolding in the documentary began in San Francisco 1973 when Chol Soo Lee was arrested for a murder he did not commit.

For the Asian American filmmakers and award-winning journalists, Julie Ha and Eugene Yi, the story of Chol and the movement it ignited was something unknown to them growing up, and what compelled them to make this documentary so it’s not forgotten or marginalized to a footnote.

“That’s another big reason why we made this film because it’s not even taught in Asian American studies at universities in America,” Julie says. “Eugene and I, we’ve always shared this passion to tell Asian American stories that are complicated with nuance and depth. It did feel like it was our generation’s responsibility to make sure this story didn’t get forgotten and buried in history.”

At the corner of Pacific and Grant in San Francisco’s Chinatown on 3 June 1973 a Chinese American with ties to the Wah Ching gang, Yip Yee Tak, was gunned down with a revolver shooting .38 special ammunition.

The police only interviewed white witnesses who were tourists that described the killer as a clean-shaven Asian man of approximate 5’10” height and 150 pounds weight. Showing the witnesses an outdated photo of Chol (evidence which was later buried), the witnesses positively identified him as the suspect. So a few days later police arrested the 21-year-old Chol who had a mustache and stood at 5’2” weighing 120 pounds. At the time of arrest, he had a revolver with .38 special ammo, but the casings did not match the murder weapon (more evidence that would be buried).

Just over a year later in 1974, Chol was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. In October 1977, while serving his sentence at Deuel Vocational Institution, Chol was involved in a fatal altercation with a white neo-nazi Morrison Needham. It was self defense for Chol, but a further trial in 1979 resulted in another guilty verdict of first-degree murder that carried a mandatory death penalty with execution by gas chamber.

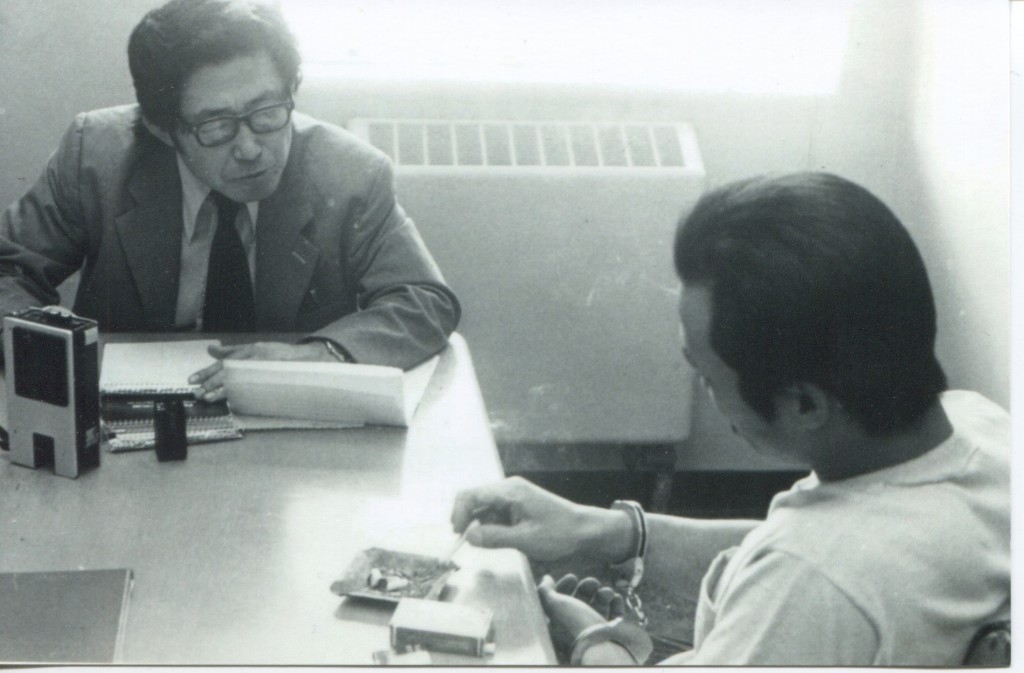

On 22 November 1977, Korean journalist Kyung Won Lee (commonly known as K.W. Lee, no relation to Chol) reached out to Chol regarding his situation. As we see in the documentary, K.W. explains his affinity for Chol who he sees as a victim of injustice, systemic racism and a vicious cycle of American institutions perpetuating ignorance and insensitivity.

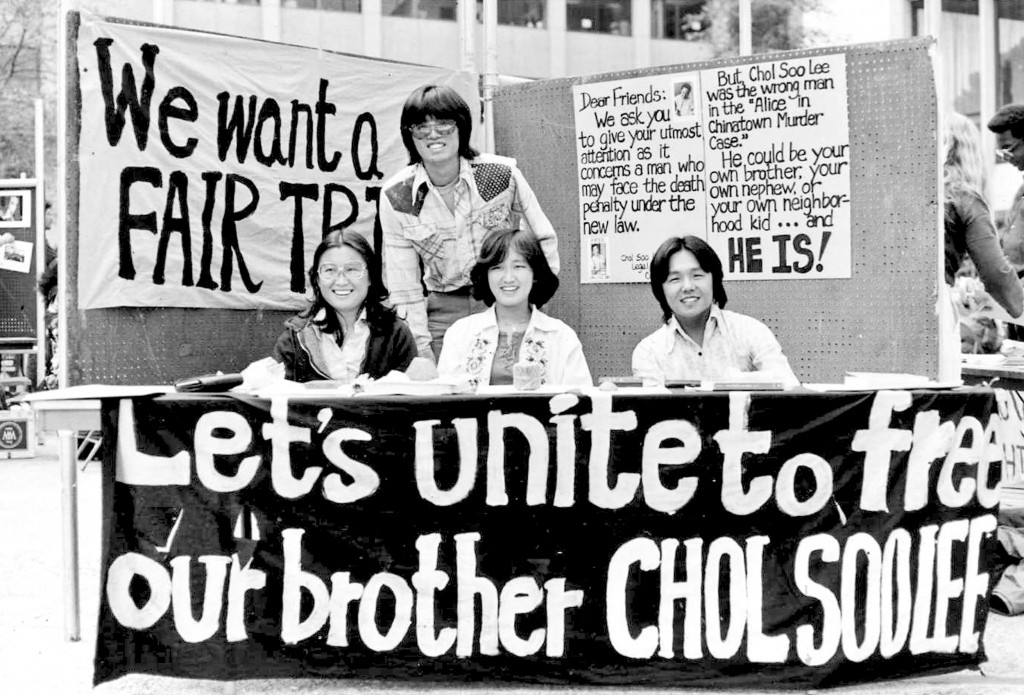

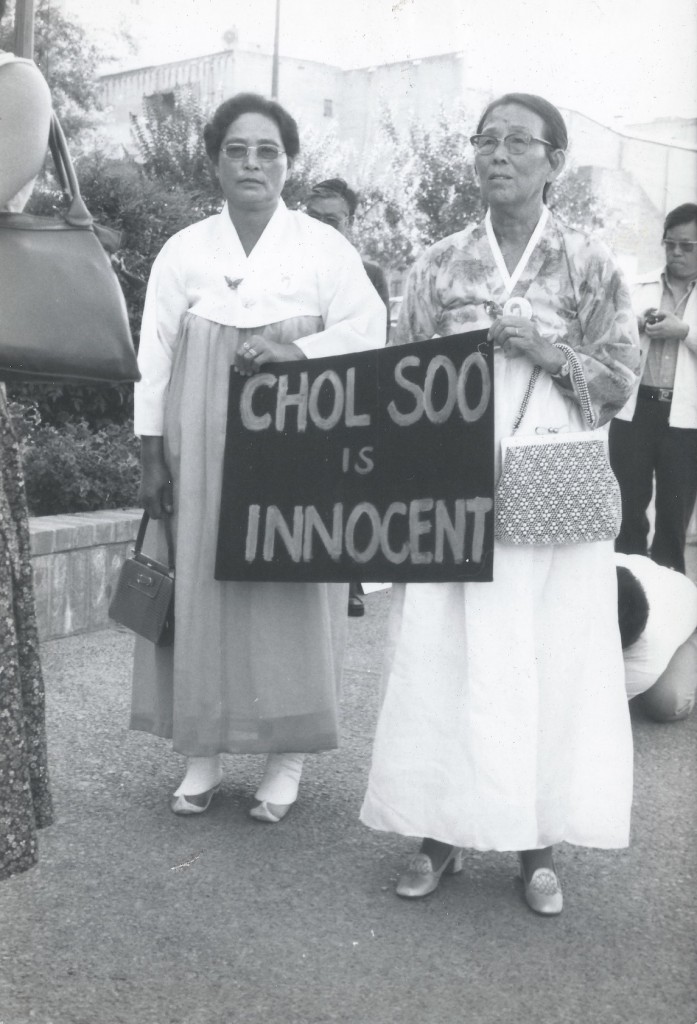

The crusade began with a two-part series Lost in a Strange Culture and Alice-in-Chinatown Murder Case published 29 and 30 January 1978, respectively, in the Sacramento Union. Writing a series of stories, K.W.’s journalism inspired activists across the state, nation and globe to the “Free Chol Soo Lee” movement. It was not just young radicals protesting either — it was multi-ethnic, multi-generational and multi-occupational from hourly laborers to prominent entrepreneurs, all of whom committed nearly a decade of activism to free Chol Soo Lee.

The campaign raised over $120,000 for Chol’s court appeals. By September 1978, the Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee hired the “Chicago Seven” defense attorney Leonard Weinglass to work on Chol’s behalf (alongside Tony Serra and Stuart Hanlon). By 1983, Chol was acquitted of Yip’s murder and had the conviction of Morrison’s murder reversed. After a decade of incarceration, he was released from prison in August 1983.

Sadly, at the age of 62, Chol passed away in 2014. It was at his funeral, which Julie attended, where the seed was firmly planted to do a documentary on Chol.

In 1990 at the age of 18, Julie was interning at Korea Times, a publication founded by K.W., whom by this point was highly distinguished with a plethora of local, state and national awards for his 30-plus years of investigative reporting. “That’s when I first learned about the case. I was inspired to be a journalist after meeting K.W.,” she says.

Julie then distinctly recalls the heaviness at Chol’s funeral: “K.W. Lee stood up at one point, and he was in such anguish, and he said, ‘why is this story still underground after all of these years — a landmark Asian American social justice movement that overturned two murder convictions, the impossible in the American justice system, and freed this man from prison! Why don’t people know about this case?’”

Eugene had known about the case through Julie as both worked together, Eugene as a writer and Julie editor-in-chief at the magazine KoreAm Journal, a publication covering Asian American culture, which ceased printing in 2015 and subsequently re-branded to Character Media. In 2015, Eugene was working as a video editor for the New York Times and felt his skills could enhance a project.

“There was always a way we collaborated that brought out sensitivity and nuance to the complicated existence of Asian Americans,” Eugene says. “I was really missing being able to tell those kinds of stories. I wanted to combine the work that I had done with editing with telling the kinds of stories that we felt needed to be told.”

And so October 2015 Julie and Eugene began work on the documentary, which took six years to complete, “a wonderful rhyme with the movement,” Eugene adds, as it was six years from K.W.’s introduction in ’77 to Chol’s release in ’83.

As we see in the documentary, the 70s and 80s as well as every step of the timeline are vividly pictured with vast archival footage from videos, photos and news interviews at the time, which is then juxtaposed with contemporary interviews of those involved looking back at themselves some 40 years ago.

Much of this archive was provided by those involved whom K.W. introduced Eugene and Julie to, which speaks volumes towards its importance with the historical record. “Archival footage doesn’t archive itself; someone has to make that choice, someone has to decide that it’s worth preserving for future generations seeing and make it part of history,” Eugene says. “Our film wouldn’t exist without their work.”

With this extensive material available, the next hurdle of making the documentary come to life was the participation of Chol. Since the documentary’s creation began after his passing, the filmmakers were blessed with Chol’s actual words.

Throughout the film, a narration is provided that is taken from Chol’s 2017 memoir, posthumously published, Freedom Without Justice. The power of Chol’s own words is extraordinary, but the brilliance is conveyed as spoken by Sebastian Yoon.

Su Kim, one of Free Chol Soo Lee’s producers, discovered Sebastian at an event he was representing, the 2019 four-part documentary series College Behind Bars. The documentary follows incarcerated men and women striving to earn college degrees through the Bard Prison Initiative, Sebastian being one of them.

Sebastian is a Korean American who at the age of 16, was sentenced to 15 years for manslaughter in the first degree, charged as an adult because at the time teenagers were still charged as adults in New York state. The documentary showcases his journey to earn a college degree whilst incarcerated.

“Su was so moved at how honest and open he was. She also felt that there was something in him that reminded her of Chol Soo Lee,” Julie says. After watching the documentary series, “[Eugene and I] were blown away ourselves.”

And so, after reaching out to Sebastian, he was intrigued by the filmmakers offer and watched an early cut of the film. “He was moved to tears after watching it; he felt a personal resonance with Chol Soo Lee’s story,” Julie says.

Another striking narrative throughout the film is the insight from Jeff Adachi. He was a student that was impassioned to be an activist for Chol Soo Lee, even helping pen a hit song, The Ballad of Chol Soo Lee, a folk-rock tune evoking the best of Bob Dylan that would help the movement go viral.

It was the activist work here that led Jeff to pursue a legal career spanning 30-plus years working in San Francisco’s public defender’s office. “If you look at his life, he was so directly affected by helping Chol Soo Lee,” Julie says. San Francisco is the only city in California that elects their public defender. Jeff won the 2002 election to be chief attorney, which he served for 15 years until he passed away in 2019. Free Chol Soo Lee is dedicated to Jeff.

Balancing their day jobs, families and constantly fundraising is all in a day’s work of an independent filmmaker, Eugene and Julie express. But now as it’s complete and Free Chol Soo Lee is out in the universe again, the filmmakers feel a sense of relief that they created a preservation of this great Asian American legacy.

“We’re not used to seeing Asian Americans in these roles,” Julie says. “You have to see it and hear it to realize that this happened and just to feel that emotion, texture and impact.”

For Eugene, Free Chol Soo Lee provides, “images of strength, of resistance, resilience and their power,” he says. “It’s able to give us roots, to fight against stereotype.”

Related Reading

@majesticdisorder

@majesticdisorder