ConSILIENT KNIGHT

In conversation with artist Jan Fabre

Written By Sean Stillmaker

In our contemporary setting, Millennials have often been characterized as the slash generation from their multitalents stretching across a diverse spectrum. During the Renaissance, the same characterization bestowed a more refined label of polymath.

For Belgium artist Jan Fabre, a polymath or Renaissance Man is certainly more appropriate as his work, thoughts and inspirations deeply resonate within the Middle Ages opposed to our wired-connected modernity.

On the eve of his solo exhibition in London, just coming off his 24-hour theater performance of Mount Olympus in Antwerp, Jan sat down over glasses of wine detailing his 30-year culmination of painting, sculpture, directing, choreography and philosophy.

Your art has been expressed across a variety of mediums, yet you dismiss the label of multimedia artist. Why is that?

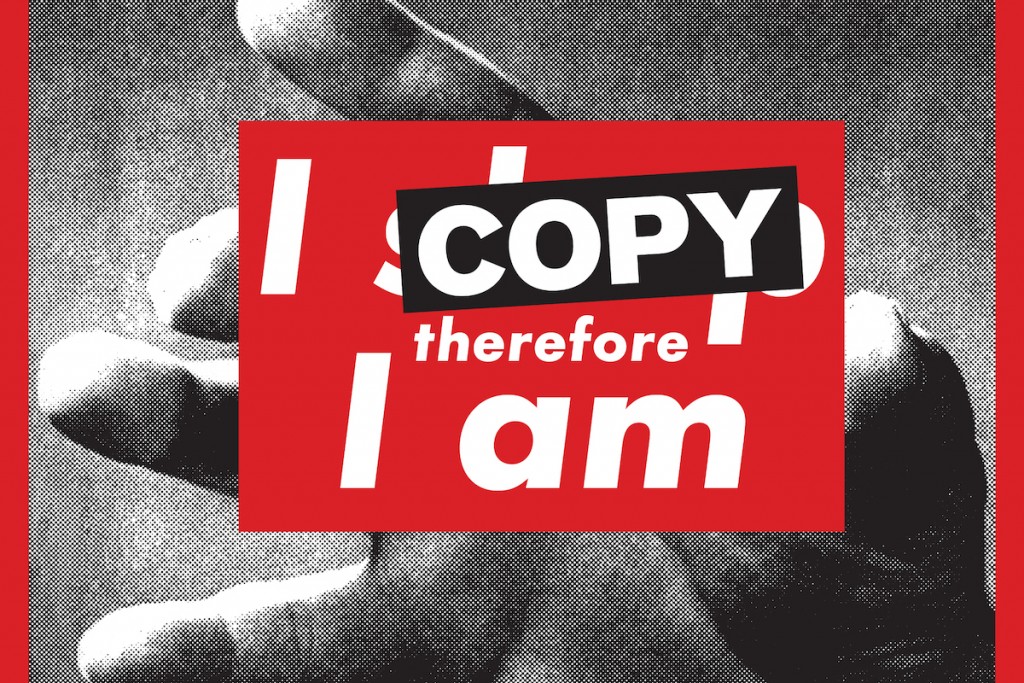

To be honest, a lot of multimedia artists, I believe, sometimes aren’t very good thinkers. I’m a consilient artist. My work over the last 30 years is clearly theater, performance or visual arts. There’s a consilience because it comes out of my brain.

(As Jan enlightened, consilience is a term introduced by Edward Wilson who is an American philosopher, biologist and entomologist. Consilience is a scientific form of study synthesizing human and animal nature whereby identifying and interpreting links).

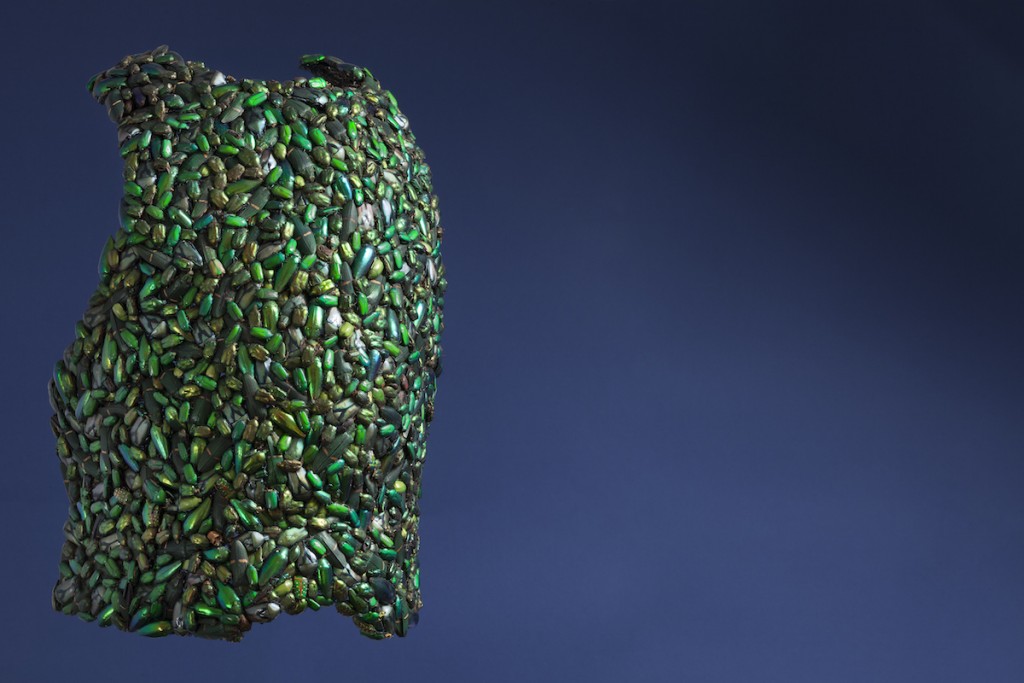

Beetles have been strongly explored and represented throughout your work. What was the root of your fascination?

When I was 17 or 18, I made my first laboratory in the garden of my parents house. Around the same period, I received books from my family about entomology. So there was free inspiration. By sitting in this laboratory in the garden, lets say, I was fascinated by the mechanics of life.

I was digging out worms, catching flies, mosquitoes, cutting off the wings and placing them on the body of the worm. I was creating, kind of, new life. Through the writings, I’ve discovered entomological worlds and then later in my studies in academia, I saw in a lot of Flemish paintings insects, their meaning and symbols. So this developed out of science and art.

Do you feel there is any symmetry between your body of work and contemporary art?

I’m an artist from the Middle Ages because I believe in beauty, I believe in humankind, I believe in vulnerability and the force and power of humankind and beauty. It’s not very fashionable to talk about these things.

The art market and art world are so impregnated by the terminology of power and cynicism. My work is completely on another side; my work takes completely different roots. My work refuses cynicism, completely. In all of contemporary art, it’s very cynical. So in that sense, I’m not such a contemporary artist.

How did you originally gravitate toward the Middle Ages for inspiration?

My parents were poor; we didn’t have a car at home. So all of my friends were playing with small cars. So my father made for me castles and fortresses that I was then always playing with. So I took this with me and later I became interested in the Middle Ages.

You’ll see in the society that we live in, there’s still a lot of signs that are from the Middle Ages. For example, the barbershop sign with the blue and red swirl that was the symbol for bloodletting. A lot of symbols we have today survived from the Middle Ages, we just don’t know them anymore.

So for me, looking toward the paintings of the late Middle Ages — they’re masterpieces, they’ve influenced me a lot. So it was all very organic.

(It was only natural this question occurred as the clashing of sword and armor appeared on the Tv screen as Jan’s performance video dressed as a knight entitled Lancelot, shot on Super 16mm film, played).

As it took over three years preparation, what was the inspiration behind Mount Olympus?

As you see in a lot of my work, the Greek metrics come back often — the theme of Prometheus and the Greek tragedies; they’re all so fantastic.

When you read Medea, it’s usually translated very badly by European theaters as a family tragedy. No, Medea is about a woman who comes from a matriarchal society and comes to a patriarchal society where men rule and women have nothing to say and kills her children. It’s like a Syrian mother today who says she would rather kill her children than let them fall into the hands of IS. That’s the story of Medea. In all of these Greek tragedies, it’s so much more cruel than what is happening today, but they’re fantastic.

For me it’s inspiring to read all of these again — the Greek tragedies, comedies and philosophers. I’m learning a lot again and that’s important. When I work as an artist I want to learn and discover a lot.

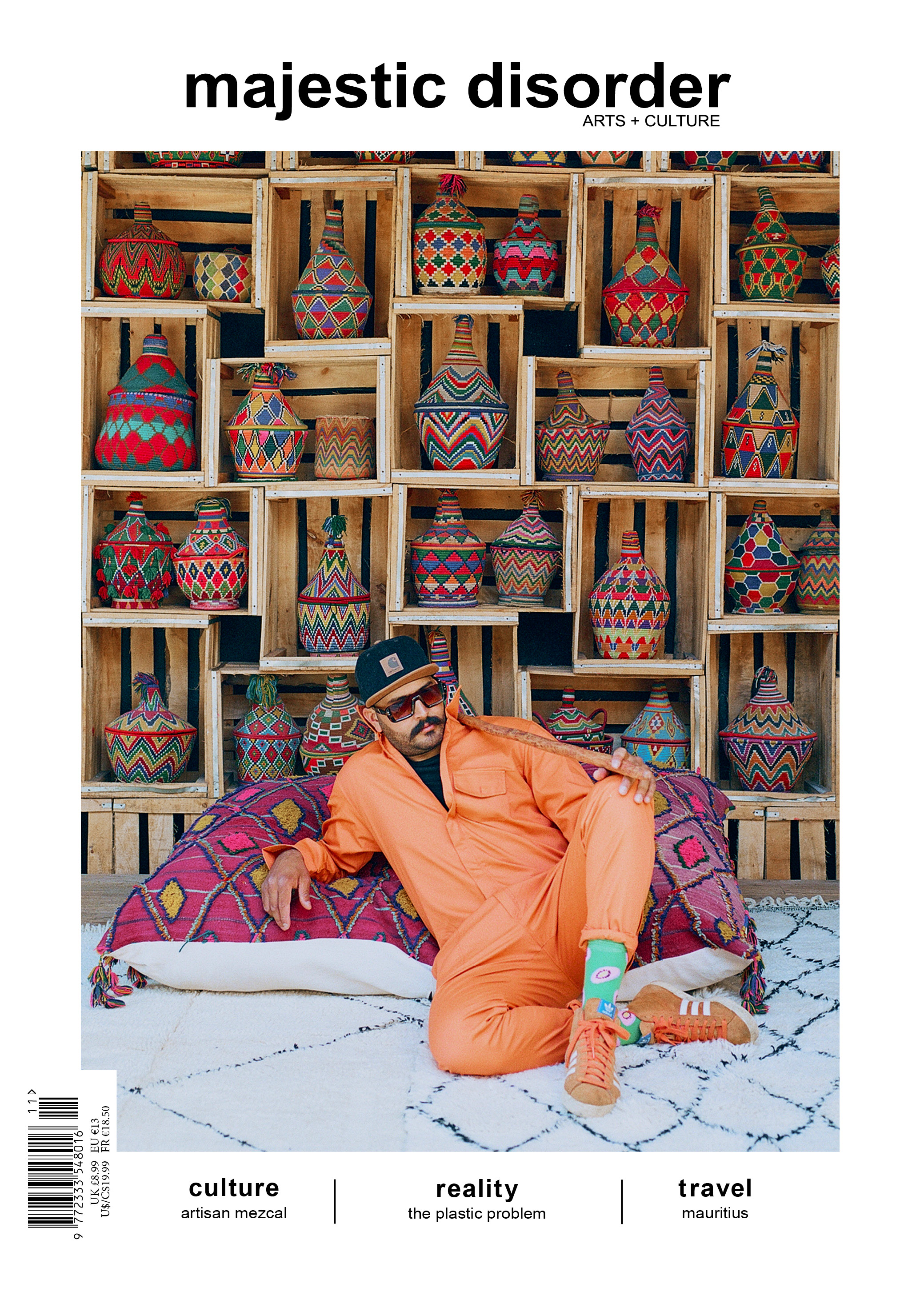

A curation of Jan’s work is available to view at the Ronchini Gallery in London.

This interview has been edited and condensed

Images c/o Jan and Ronchini Gallery

Related Reading

@majesticdisorder

@majesticdisorder