fascination & fear

How SUPERFLEX combines art and social responsibility

Written By Sean Stillmaker

The numerical value system of commodified mediums holds no interest to SUPERFLEX. The only commodities that fascinate this unique Danish art collective are ideas with societal impact for positive change.

Since founding the group in 1993, Jakob Fenger, Rasmus Nielsen and Bjørnstjerne Christiansen, have been developing ideas and producing projects around the world, which they refer to as tools — communicative, empowering models that can be modified.

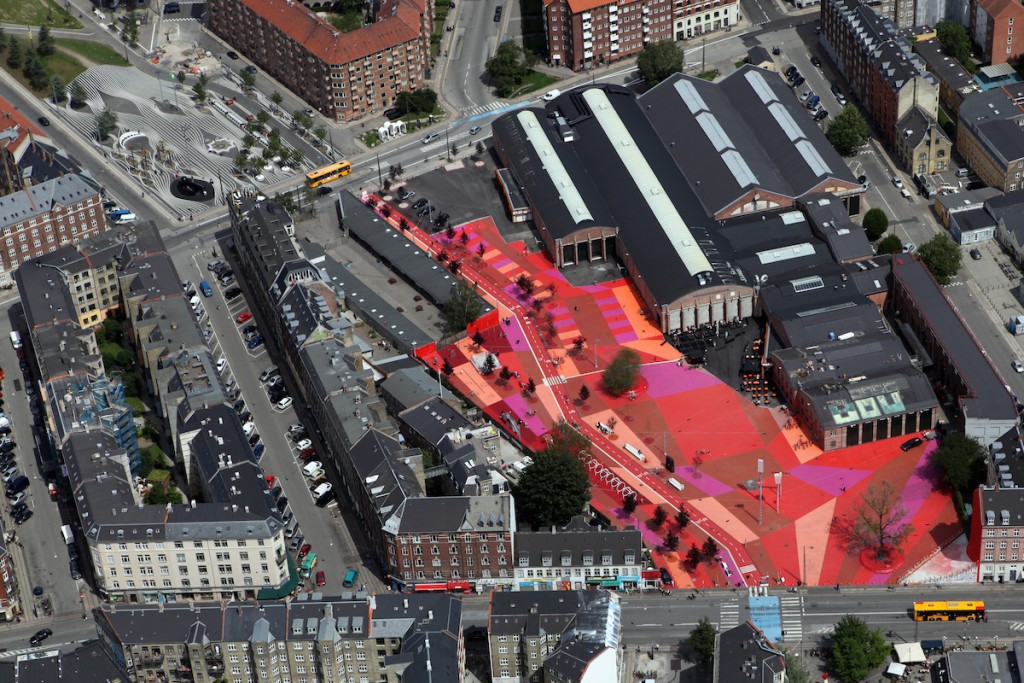

From building sustainable energy sources in developing nations and producing Brazilian farmers’ guaraná soft drink to creating Copenhagen’s tastefully artistic public park that represents over 50 nationalities, SUPERFLEX has always decided to be part of a solution rather than indifferent to the problem.

Sitting down in Copenhagen, SUPERFLEX details the inspirations behind their work. This interview is an excerpt; the full published story can be read in issue 5.

What has been the guiding principle for SUPERFLEX?

I think our way of approach is 50 percent fascination and 50 percent fear. You look at something, and you’re fascinated by it and you want to do something. From our perspective, it’s always been interesting to work in a social context.

And also working in a social context where you put yourself on the table, so to speak, where you become part of the problem or part of the solution. So instead of staying outside and looking in, you’re more interested actually going into the situation and knowing you can be wounded in that same situation.

Later on, this fear was something added onto it. Like, when we did our work on Bankrupt Banks, it’s huge research on all the banks in 2008 that collapsed and how and who bought them up afterwards. You would think you would be doing an A4 page of all the banks, but you end up doing a book. I think that amount and that power of the whole system, and the way it’s not transparent, it’s very, very scary.

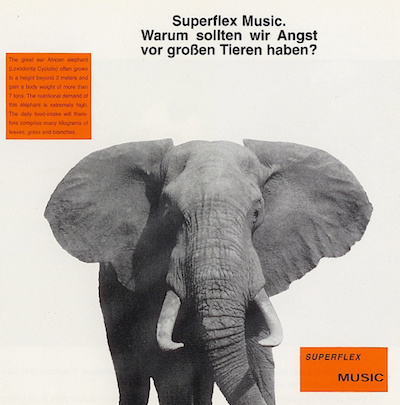

Since the beginning, the global financial system has always been an area of fascination. When SUPERFLEX had a record label, the first LP was designed after a German bank brochure. Where do you feel this system is heading?

There’s definitely more waves to come. It’s almost like scientology, where you get to these levels like OT5, OT7. It’s like a system, but I don’t know if anyone knows the ending of it. In 2009, we did this film called The Financial Crisis, and it was based on the idea that this whole crisis was a psychosis, so we were treating it as such.

We have a good friend that’s a banker and we were actually talking about this — limited and unlimited. You have two kinds of banking systems, the old-school banking system is unlimited, which means the owner of the bank would have unlimited responsibility for whatever happened to the bank.

Meaning that if I were to own the bank, the bank goes bankrupt, I would lose whatever I had — everything. Accountability, that’s another word. But today, that doesn’t exist anymore. Today, it’s all managers who have limited responsibility, which means they’ll just get another job.

They may lose one month’s paycheck, that rarely happens, most of the time they get a golden handshake.

It’s kind of a weird system where it seems like there’s absolutely no control and no way the system can stop because everything is this limited responsibility, and that’s been taken to another level now, which is interesting.

SUPERFLEX has successfully navigated complex systems, like municipal project development with Copenhagen’s Superkilen Park, which was a 2013 finalist for the Mies Van Der Rohe award. What was the most challenging throughout the project?

When you do these kinds of projects, it’s always happening through these community meetings, which are set up by the city council and the architects, most of the time. We found them extremely limited.

You would be in these meetings and it would be mostly men in the ages of 50-60. Most of them would be complainers, because they don’t want the change, and they would be the ones who actually would have something to say about the project.

After the meeting, you’d go to the street and you’d see all the kids, and you see a lot of other people who never went to the meetings.

So we came up with another strategy. We called it Participation Extreme, taking from the TV show in the States calledExtreme Makeover, which is a terrible TV program.

There was something nice to that though; there’s something about the energy. We wanted to take that energy and put that on the city council.

So we got money from art funding to invite people to travel. Through our network, we know different groups and people in the neighborhood working with kids who are producing music, sports, different kinds of things. So we’d go to them and say ‘OK, let’s discuss what you’d like to have, and let’s see what we can do about it.’

Then someone said, ‘I’d really like to go to Jamaica to get a sound system because that’s what we really need here in this town. OK, let’s go.’ So this kind of energy where somebody would propose something, and then we would go. Literally, this guy went to Kingston with two kids to look at sound systems …

We see it more as a model or as an example of a way to approach things, not as a solution to any problem. So next time it maybe a completely different approach.

Related Reading

@majesticdisorder

@majesticdisorder