exporting iranian street art

The political battle on Tehran’s urban space and the street artists who

risk freedom of expression with their artistic commentary

Written By Kira Harada-Stone

The emerging urban city of Tehran, home to over 8 million people, is filled with modern nuances from the towering glass façade of the central bank to the rotating residential apartment Sharifi-Ha house. The mundane streets and drab buildings are livened with vibrant murals, created with the skill and precision of a worldly street artist.

But looks can be deceiving.

“Walls are powerful medias,” says Ghalamdar, a former Iranian street artist, now residing within the UK.

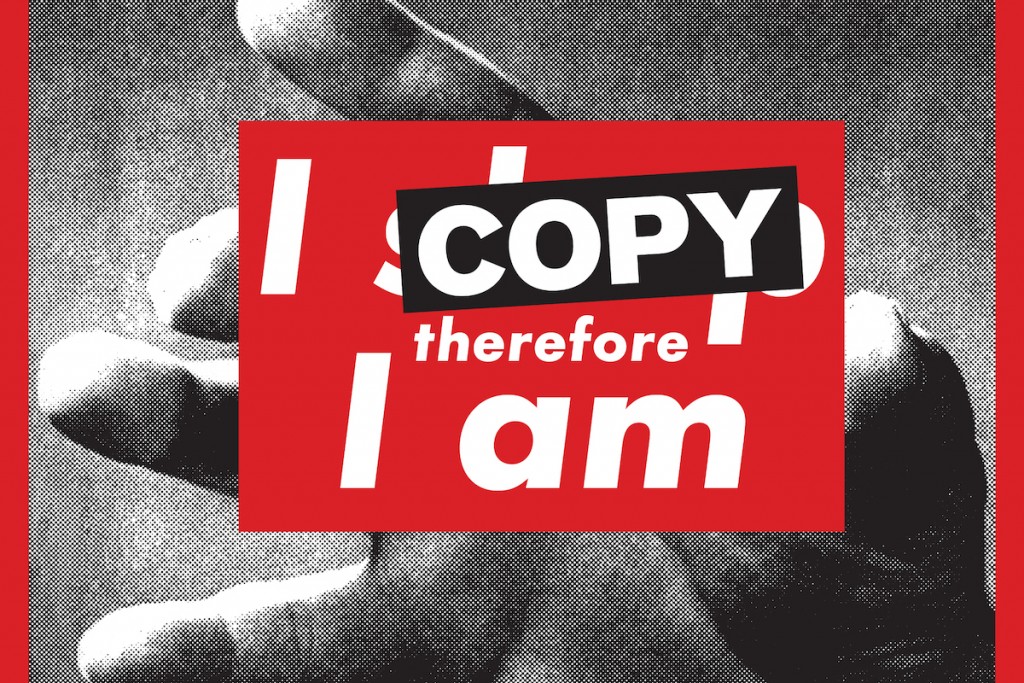

“The regime is still using the public spaces to control the public mind and to advertise it’s Islamic propaganda. The base and root of graffiti and street art in Iran is absolutely political.”

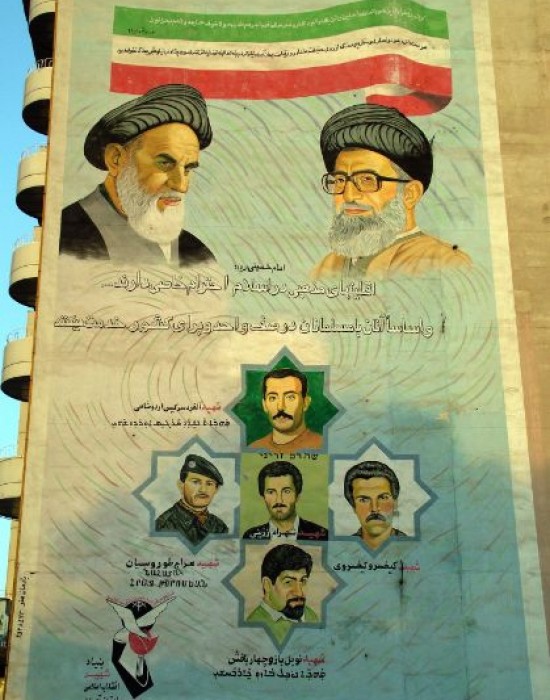

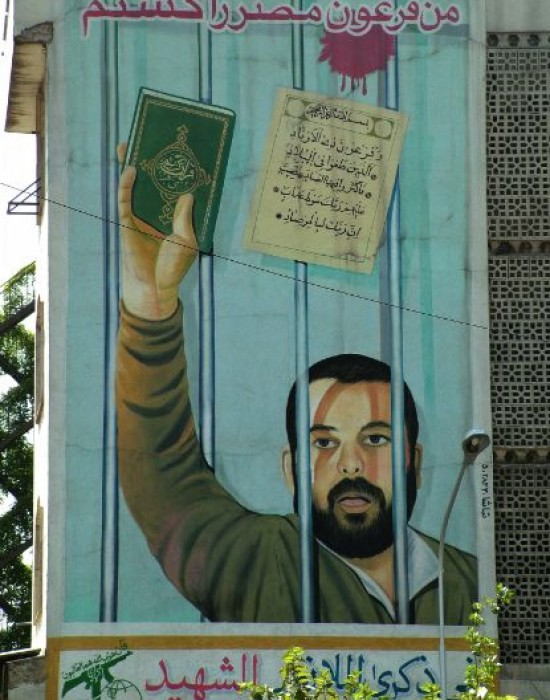

The massive murals methodically positioned around Tehran depict victorious leaders of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, symbols of martyrdom and Shia Islamic iconography, many of which are commissioned by the government.

Creating such murals accelerated in the late 80s under Tehran’s then-mayor Gholamhossein Karbaschi as a way to improve the urban landscape as it was rife with graffiti. This policy was also implemented concurrently in NYC under then-mayor Ed Koch, who credited the city’s prosperity to the policy, which initially developed as the broken windows theory.

“Iranian art has always been urban,” says Dr. Sussan Babaie, who was born in Tehran and now teaches about Iranian and Islamic art at the Courtauld Institute of Art. “These habits have to do with what the urban environment bears for us. What do we see when we drive around?”

The ability to publically express any viewpoint that conflicts or dissents from the Islamic Republic, however, is ambiguously forbidden. The laws in place do not specify charges against graffiti or vandalism, but they can be interpreted as crimes against the state or irreverence to religious sanctities, which carries punishments ranging from imprisonment, fines or lashings.

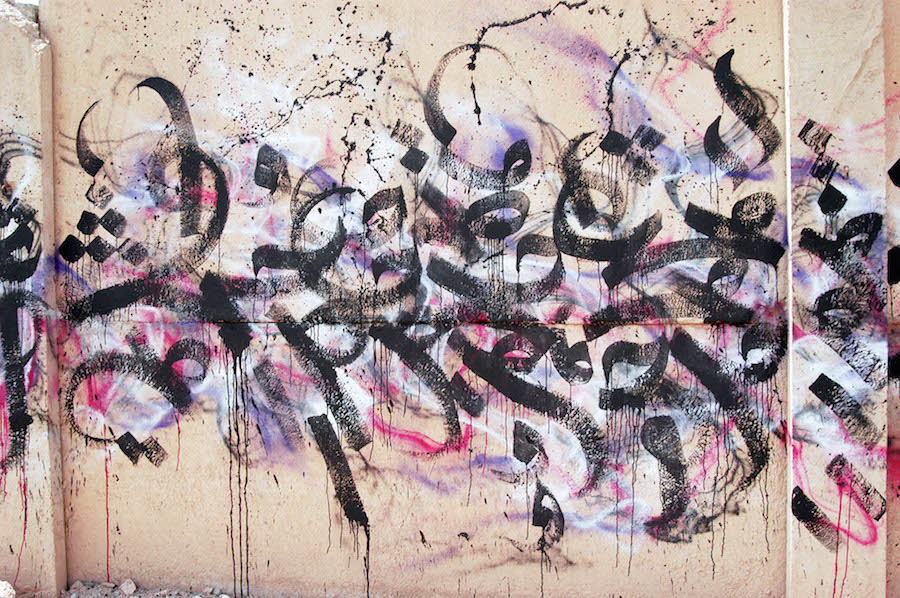

For Ghalamdar, 21, he has envisioned his place within Iran’s street art world as an ambassador of “calligraffiti,” an artistic style that combines traditional Arabic calligraphy with modern graffiti. After becoming involved in street art as a kid, he spent several years perfecting his risky craft. His tag is Ghalamdar, which translates to “the writer” in Farsi, he keeps his actual identity in a tight circle.

“I just wanted to add color to my gray hometown, Tehran, and break the habit of watching the same walls I passed by everyday,” he says. “I’ve always been inspired by the Arabic traditional calligraphy and Iranian miniature painting, therefore I found the Saqqakhaneh [Iranian art] movement very inspiring. I find my roots in the vandalisms of the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and the Saqqakhaneh.”

Soon enough, he began using his work for political expression, seeking inspiration from his predecessors of the revolution.

“When the regime is against thinking and creativity and is trying to transform the society, art and culture becomes a form of resistance. Iranians are the nation who made a revolution happen with graffiti.”

At the age of 15, Ghalamdar and a friend were arrested for attempting to spray stencils of figures that were involved in the Green Movement of 2009, he vividly recalls.

“Suddenly they came out of nowhere and forced us to get into their car,” says Ghalamdar, who was then blindfolded. “They took us to an unknown location for interrogating and asked us nonsense like, ‘Are you in touch with Israel? Where are you trained?’ It was a long interrogation. They released us, as we were so young, but it was too heavy for a 15 year old boy.”

While Ghalamdar did not let the regime stifle his artistic abilities, he did make the decision to leave Tehran, having arrived in the UK last month to continue his artistic commentary.

“It’s so interesting to see how these artists were taking risks to focus on social, cultural and political issues,” says Shaghayegh Cyrous who curated the recent Iranian Urban Art exhibition at Graffik Gallery in London, which Ghalamdar was part of. “Ordinary people in Iran do not have time to think about them. They take the risk to paint over the city to remind people about these kinds of issues.”

Still undertaking the risk in Iran are street artists like Ill and Mad. Although they understand the risk and censored environment they work in, it’s because of those limitations they feel fuel their work.

“Once you get caught it feels horrible because you don’t have any idea of what you will be facing,” says Ill, who has been arrested three times, but has been lucky enough to get out of each situation, he added.

“They don’t know what they will charge you with, irrelevant crimes such as satanism, vandalism, national security etc … It’s mostly political, the reason being is that writing on the wall reminds them of the Islamic Revolution because writing slogans on the walls was something people used to bring down the Shah,” Ill says.

Although limited in global mobility compared to renowned street artists, the two are able to spread their work and messages around the world by sending their stencil designs to friends throughout the US and France. Through their friends Icy and Sot, formerly of Tabriz, Iran who relocated to the US, Ill and Mad’s work have been popping up around NYC and Brooklyn.

Continuing the commentary in London will be work from Ghalamdar.

“Graffiti itself is in exile,” says Ghalamdar. “I left because I couldn’t work in Iran anymore … People told me that I lost everything I had. The only thing I had to tell was that I came here with a bag full of culture. That’s the only thing I have and I need to save it.”

Iranian murals photographed by Fotini Christia, courtesy of Harvard Library

Calligraffiti photos courtesy of Ghalamdar

Related Reading

@majesticdisorder

@majesticdisorder